Part 2, C’mon down: Federal land management agencies have been unable to contain the damage that tourism and outdoor recreation has inflicted on once-pristine public land. What’s changed?

Part 3, Co-management vs. cooperative management: The differences are substantial, but tend to be conflated in service of political agendas.

Part 4, Toward true “co-management" in Montana: Pitfalls and possibilities (Blackfeet attempt to re-claim Badger-Two Medicine south of Glacier National Park and Salish-Kootenai purchase Kerr Dam on the Flathead River).

Part 5, Tribal perspectives at the forefront: An acknowledgment of the Biden administration rooted in the fact that Bears Ears coalition tribes consider the area sacred.

Part 6, Priorities: The BLM and Forest Service say they'll safeguard "objects" within the monument and "values" associated with the monument. Recreation access has second-tier status.

Part 7, Historical suspicions: Effective federal management to protect the Bears Ears region's artifacts, unique geological formations, plants and wildlife would have to overcome deeply ingrained skepticism.

(Parts of this report were published by City Weekly.)

Part 1

On May 10, 1869, crews working for the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads completed the nation’s first transcontinental rail line at Promontory Summit in northern Utah, a historic achievement in the development of the United States and one that is indelibly etched into the psyche of the West’s Indigenous peoples.

The story is expressed in many ways across Indian Country, perhaps most beautifully and poignantly through the traditional art of Navajo weavers. Many pieces—including some that are now priceless, museum-caliber heirlooms—depict locomotives chugging across the sage landscape, benignly interspersed among ancient symbols and motifs. The strands of wool are dyed from extracts of native plants and then threaded through a loom one at a time by an elder preserving a uniquely American art form.

A darker interpretation involves the dreams of spiritual leaders: of trains rumbling unstoppable through wildlands, destroying everything and everyone in its path.

“They tell a compelling story of adaptation, survival and change by the Navajo people,” said Kim Ivey, a senior curator at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, quoted by the Virginia-Pilot in a story about an exhibit there on Navajo weavings. “The trains arrived in the 1880s, and it changed the Navajos’ lives forever.”

Both perspectives forewarn of cultural displacement, even genocide. In one, trains and their passengers are newcomers, arriving or passing through from distant areas unknown.

The other suggests an invasive species with the power to destroy an ancient way of life and the ecosystem it depends on. They’re coming to drill for dead dinosaurs, dig for treasure, cut down trees and tromp around on life-sustaining plants and soil for their recreation, unwittingly destroying the remaining habitat that sustains some of America’s most magnificent creatures.

They’ll call it “progress.”

Many Indigenous peoples have embraced the allegory, or variations, passed down over generations. Perhaps, to a certain extent, the current federal government has as well.

Over the past year or so, the Biden administration has trumpeted its commitment to re-framing policy initiatives surrounding the government's fraught relationship with Native Americans, including management of the president's new version of the Bears Ears National Monument. In 2021, Biden chucked President Trump's scaled-down version of the monument and restored and expanded President Obama's 1.3 million-acre preserve.

And on June 18, officials with Biden's Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service together with leaders of tribes with ancestral ties to Bears Ears – the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation and the Pueblo of Zuni – ceremonially adopted an Inter-Governmental CooperativeAgreement.

It was called "unprecedented," a publicly prominent next step after Biden's restoration to solicit and incorporate tribal points of view into federal management plans.

The agreement represents "what true Tribal co-management should look like," Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, said at the time, "sharing in the decisions and management plan with federal investments to supplement efforts. This is one step in how we honor our nation-to-nation relationships with Tribes."

The pact came several months after what was billed as the "White House Tribal Nations Summit." Biden, known affectionately as "Uncle Joe" to many Navajos, announced that the departments of Interior and Agriculture had created something called the "Tribal Homelands Initiative." Haaland and Tom Vilsack, Agriculture secretary, formalized the concept with a directive from on high called the "Joint Secretarial Order on Fulfilling the Trust Responsibility to Indian Tribes in the Stewardship of Federal Lands and Water."

Patrick Gonzales-Rogers, former executive director of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, which was formed in 2015 to represent the five tribes, said there has been a dramatic shift since Joe Biden won the presidency.

“Now we have a reset. Within days of Biden winning the election and then getting a transitional transition team in place, there was already a reach out,” he said, noting “there was a day-and-night difference in terms of the responsibility and the basic engagement” between the Trump and Biden Administrations.

“Yes, the Bears Ears represents one of the premier public land’s issues. And then when you intersect it against environmental social justice, it’s probably the premier issue because you have the combination of these two big puzzle pieces. But the reflection of what is due to the tribes was not lost on the Biden administration. And there was an immediate kind of change in the complexion, constitution, and comportment on how they were going to engage the tribe.”

However, given pressures exerted at the 30,000-foot level by partisan politics and seemingly unresolvable cultural conflicts—among them RVers at the ground level who just want a flat space in a mountain meadow to escape for a week—it’s an open question whether the federal lands-management bureaucracy has the capability to take effective action on non-tribal, publicly held land in southeast Utah. Or anywhere else.

Adding fuel to the fire is the state of Utah.

Republican

leadership here has long chafed at the scale of federal land ownership

within the Beehive State, and, in August, Utah filed suit against

President Biden and top-level land managers in an effort to scuttle the

president’s expansion of the monument’s boundaries—a long-predicted

tit-for-tat following lawsuits in 2017 that challenged Trump’s ability

to shrink Obama’s original designation.

Utah’s litigation alleges

that the Biden administration violated the Antiquities Act in expanding

Bears Ears, as the act stipulates that protected areas be as small as

possible, “compatible with proper care and management.” A private law

firm from Virginia, Consovoy McCarthy, has been hired to represent the

state alongside government attorneys. Other clients of the firm

include Donald Trump.

“These public lands and sacred sites are a

stewardship that none of us take lightly,” Utah’s governor, lieutenant

governor, state auditor, legislative leaders, congressional delegation

and U.S. senators—all Republicans—said in a joint statement announcing

the state’s lawsuit. “The archaeological, paleontological, religious,

recreational and geologic values need to be harmonized and protected.”

They

continued: “Rather than guarding those resources, President Biden’s

unlawful designations place them all at greater risk. The vast size of

the expanded Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national

monuments draws unmanageable visitation levels to these lands without

providing any of the tools necessary to adequately conserve and

necessary to adequately conserve and protect these resources.”

Redge Johnson, executive director of the Governor’s Public Lands Policy Coordinating Office in Utah, suggests the state may find support within the federal judiciary – even at the Supreme Court.

___________

C'mon down

Part 2

Like many of the most exquisite, environmentally sensitive spots in western United States, Lake Tahoe has been transformed by the post-World War II boom in tourism and outdoor recreation: tens of thousands of tourists pondering kitsch and posing for selfies; flashing lights, bells, whistles of slot-machine hubbub on the Nevada side; mega-mansions behind gates monitored by video cameras and security guards protecting property of absentee owners who split their time between Tahoe and the world's commercial and entertainment centers; hyper-inflated real estate prices; gargantuan hotel and condominium developments; burger flippers making $10 per hour and sharing two bedrooms with six others for a memorable summer.

Lake Tahoe is fed by the Truckee River from its source in the high Sierra Nevada and flows into Upper Truckee Marsh at the south end of the lake . The marsh is the primary filter for river water entering the lake.

The system has produced water clarity unmatched anywhere in North America, possibly the world. For eons.

It’s measured simply by submerging a disk until it’s no longer visible. Currently, that depth is a remarkable 70 feet. But a few years ago, it was 90 feet and more.

Commercial development along Tahoe’s shores and within the lakes’s basin is taking its toll.

During the 1960s, long before California's stringent environmental laws were enacted, a marina community known as Tahoe Keys was built in the marsh, the filter. Owners of roughly 1,500 homes and townhouses, many with private docks, were afforded direct access to Tahoe's 70-mile shoreline through about 11 miles of interlocking canals and lagoons scooped out of the wetlands.

Tahoe Keys' decades-long demolition of an ecosystem can be mitigated only through extraordinarily expensive litigation and political heroism. Who knows? Every other automobile around the lake sports a “Keep Tahoe Blue” bumper sticker. “Sustainability” seems to be something more than a politically correct buzzword.

But the Truckee keeps on truckin', cutting an alpine and sage canyon beginning at a shallow outlet at the lake's northwest end, bisecting Reno and continuing east through the desert to its terminus about 120 miles downstream of Tahoe on the Pyramid Lake Paiute reservation (Cui-ui Ticutta).

Pyramid Lake (Cui-ui Panunadu to the Paiutes, meaning fish in standing water) is quiet, commercially primitive, other-worldly. It constantly changes color from shades of turquoise or gray depending upon the skies above and varying angles of seasonal light. It's the only habitat in the world for Cui-ui, a large sucker-like species that's been swimming those waters for 2 million years. Its fishery includes world-famous Lahontan cutthroat trout, and the lake is home to a large colony of American white pelicans.

The lake would still be recognizable to Paiute elders across time.

The tribe's relative success at defending their land against tourists, miners and farmers is unusual, but not unique. Taos (New Mexico) Pueblo, the Navajo Nation, Northwestern Band of Shoshone of northern Utah, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Blackfeet Nation of northwestern Montana and other tribes also have recognized the downside of tourism and commercial development: overloaded infrastructure, damage to nature and threats to their culture and heritage.

Each tribe, given their unique circumstances, found the wherewithal to fend off a bit of the onslaught by limiting or even banning tourism and related commercial activities, regulating the supply of accommodations, preventing infrastructure development and purchasing sacred land.

The growing political clout nationally of Native Americans reclaiming their ancestral land and preservation of their culture and spirituality - in many ways their identities - holds important lessons in the effort to mitigate on-going damage to the Cedar Mesa (aka Bears Ears) region of southeastern Utah.

It's not unusual for Pyramid Lake Paiutes to close off much of their lake's shoreline, temporarily and even permanently, to prevent vandalism of its spectacular tufa formations believed to be physical incarnations of legend. (Tufa is a rock composed of calcium carbonate that forms at the mouth of a spring, from lake water, or from a mixture of spring and lake water.)

Taos Pueblo sealed off their sacred Blue Lake in the Sangre de Cristo range of northern New Mexico to non-tribal recreationists. The Navajo Nation limits climbing its iconic spires and cliffs and, a few years ago, voted down a multimillion-dollar development above the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado in the northwestern corner of the reservation that would've shuttled up to 10,000 visitors a day to the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

In January of 2018, the Northwestern Band of Shoshone purchased 550 acres at the site of the Bear River (Boi ogoi, big river) Massacre for a reported $1.7 million.

A statue at the Fort Douglas Military Museum on the campus of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City commemorates Patrick Connor, who led soldiers in that 1863 massacre of Shoshone men, women and children.

The largely forgotten atrocity was quite possibly the deadliest of the Indian war era. On the morning of Jan. 29, 1863, a group of 200 soldiers posted at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City under the command of Connor killed between 250 and 500 Shoshone , including at least 90 women, children and infants.

A statue of Patrick Connor at the Fort Douglas Military Museum on the campus of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Connor led what many historians believe was the worst atrocity of the Indian war period.

"None of those bodies in the massacre were buried," said Darren Parry, a tribal leader. "It's sacred land to us."

The tribes often invoke claims of sovereignty over their tribal lands, which can take decades to resolve.

For example, after negotiations that began in 1980, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes purchased in 2018 Kerr Dam (Seli' Ksanka Qlispe') on the Flathead Indian Reservation downstream of Flathead Lake in Montana. The tribes paid Northwestern Energy $18.3 million for the dam, becoming the first Native Americans in the country to own a major hydro-electric dam.

Despite tribal opposition, the dam was built and completed in 1938 at a spot on the Flathead River considered sacred called the "Place of the Falling Waters" (Nowadays, a series of rapids just below the dam, part of the "falling waters," attract whitewater recreationists).

Salish and Kootenai tribal members at Kerr Dam shortly after it was completed in the 1930s

Similarly, Taos (N.M) Pueblo celebrated in 2020 the 50th anniversary of federal government recognition of the tribe's claim to Blue Lake, one of several in the mountains considered sacred, and its return. In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt, lionized for his pioneering environmental sensibilities, created the Carson National Forest.

It only took a stroke of a pen for him to seize tens of thousands of acres belonging to Taos Pueblo, including Blue Lake, but 114 years for them to get it back with the help of President Richard Nixon and his stroke of a pen.

It might take just as long, if ever, before the tribe's claim to other sacred sites are realized. Taos Ski Valley, with a long-term lease on Forest Service land, has a chairlift that whisks thousands of skiers each season to the top of Kachina Peak. At 12,841 feet, it's an important spiritual landmark for the people of Taos Pueblo.

These efforts provide models of aggressive sustainability and, theoretically, could be applied to management of Bears Ears National Monument.

However, the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service have been

unable to contain the collateral damage that tourist traps – adjacent to Lake Tahoe, but also Ketchum, Idaho, Jackson, Wyo., Park City and

Moab in Utah and on and on – have

inflicted on nearby, once-pristine public land across the West. And that says nothing about BLM’s role in facilitating development of oil, gas and mining and the Forest Service’s mission to “harvest” timber, both legally mandated, both anathema to conservation.

More often than not, BLM Utah's Canyon Country District relies on voluntary compliance of its rules, such as asking climbers (respectfully) in the Indian Creek area of the monument to avoid walls near nests of peregrine falcons, eagles and other raptors.

"Voluntarily avoiding climbing routes with historical and active nests helps protect raptors and reduces the need for mandatory restrictions," according to an Aug. 19, 2022, press release.

BLM and Forest Service staffers and a citizen advisory panel, formally named the Bears Ears Monument Advisory Committee, or MAC, met four times between June 2019 and June 2021 to discuss issues related to management of the monument. Virtually every exchange focused on damage to cultural artifacts, vegetation and geological formations and mitigation of that damage caused mainly by campers.

Yet the Trump-appointed panel was reluctant to recommend wholesale closure of the monument to so-called "dispersed" (undeveloped) camping, which taps the appeal of sleeping outside of a formal, designated campground and finding a bit of solitude and wild beauty. It's also easier to find campsite at the last minute when you're not dealing with a reservation system at a state- or national-park campground.

Out-of-the-way spots in Bears Ears don't come with the amenities of a developed campground, like water, toilets, picnic tables, bear boxes or dumpsters for trash. Therein lies the rub.

These comments, from the October 2020 meeting of the MAC, are representative:

- Gail Johnson (a MAC member): Some of the areas are becoming decimated, and people are going farther and farther in.

- Brian Murdock (Forest Service recreation planner): It is open country up there and we are seeing 4-wheelers, ATVs, and people driving cross-country right out of their campsite and not sticking to designated roads.

Christopher Ketcham, in a broadside evoking the spirit of writer Edward Abbey titled This Land: How Cowboys, Capitalism, and Corruption Are Ruining the American West, points to numerous recent instances in which the BLM backed down when faced with flagrant violations of environmental law by militant, anti-government extremists.

A prominent example is Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy's armed standoff in 2014 with BLM over his refusal to pay grazing fees. It ended only when law enforcers withdrew. A bloodbath was averted, but Bundy continues to break the law with impunity. Flora and fauna on that range has been devastated, according to Ketcham.

At this point, nothing much has changed within the BLM under Biden's administration to stop the trashing, looting, grave robbing and vandalism of Bears Ears , which were primary motivating factors behind the monument's creation.

________

Part 3

At a hearing in March before the House Committee on Natural Resources, Charles F. Sams III, director of the National Park Service and a Cayuse and Walla Walla tribal member, outlined what NPS and its massive mothership, the Department of Interior, were doing to comply with the secretary's directive unveiled at the White House Tribal Nations Summit of Nov. 15, 2021, that charts an ambitious overhaul of the federal government's relationship with tribal nations – recognizing "that federal lands were previously owned and managed by Indian Tribes and that these lands and waters contain cultural and natural resources of significance and value to Indian Tribes and their citizens; including sacred religious sites, burial sites, wildlife, and sources of Indigenous foods and medicines."

Bears Ears National Monument, for example, was created using the authority of the Antiquities Act, a process that's controversial because it dodges legislative scrutiny. No public hearings are required; no congressional votes tallied; and no favor of local elected officials or residents to curry. Protection of public lands using the authority of the Antiquities Act requires only a presidential signature.

Use of the 116-year-old act limits the scope of possible tribal involvement in monument management and erects obstacles to building trust among tribes and other stakeholders. President Clinton's unilateral decision in 1996 to create the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument remains politically toxic decades later.

The (small "d") democratic way to protect Bears Ears would include a proposal debated, voted on, approved by Congress then signed into law by the president. That route has been unanimously endorsed by Utah's political leadership at every level. It would only be subject to modification if it

failed to pass constitutional muster of appellate courts. Any larger tribal

role (say, decision-making authority equal to that of the Forest Service or

BLM) would require an act of Congress instead of just the president's signature using the Antiquities Act.

Rhetoric from tribal activists and even Interior's Haaland conflates "cooperative management" and "collaborative management" with "co-management." According to Sams, the majority of NPS working relationships with tribal nations are collaborative or cooperative rather than co-managed, and are supported through formal and legal agreements.

Operative phrases buried in Biden’s (and Obama’s) Bears Ears proclamations, the monument's interim management plan and the cooperative agreement include things like needing "to obtain input" from tribes; "guidance and recommendations" from tribes; and to "rely upon for recommendations" of tribes.

The language makes clear that Tribes play advisory roles, not governing ones. The federal government can (and does) heed or ignore tribal advice based on myriad factors, including politically and ideologically driven priorities, science with varying degrees of validity, byzantine administrative rules and bureaucratic interpretations of those rules, unfathomably baroque environmental regulations, special-interest lobbying and litigation risk.

For example, Obama's Interior Department OK'd the Utah monument toward the end of his presidency based on a blueprint of sorts developed collaboratively by San Juan County residents from a range of backgrounds who formed what they called the "Public Lands Council.” It was part of a grand but ultimately unsuccessful package of legislation introduced into Congress put together by former Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah. Hard-edged political considerations, realpolitik, related to preserving the Antiquities Act played a decisive role in the monument’s creation, according to Tommy Beaudreau, chief of staff of Obama's Interior Secretary Sally Jewell. Beaudreau's candid remarks were made during a panel discussion at Johns Hopkins University in 2018 (about 1:00:20 in the video).

“We tried to hew to the PLI (San Juan County Lands Council’s) proposal. We couldn’t argue with a straight face that there wasn’t consensus about the area,” Beaudreau said.

Tribal representatives rejected that process, and the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition submitted to Obama's Interior Department in October 2015 a proposal of their own. A primary architect of the strategy was University of Colorado law professor Charles Wilkinson. Wilkinson is a member of the Grand Canyon Trust Board of Trustees, one of several prominent environmental nonprofits that helped out with technical and administrative assistance in creation of the tribes' monument proposal. He also helped draft Clinton's presidential proclamation creating the Grand Staircase-Escalante monument.

All monument planning, policy development and staff management would've been controlled by a new entity called "Bears Ears Management Commission." No role for the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service or state and local governments was envisioned. Funding would've come from private-sector sources, according to the proposal, possibly opening a virtual Pandora's Box of conflicts of interest. The plan could've violated innumerable state and national laws and thrown a monkey wrench into existing protocols hammered out over the years between agencies and various interests that govern day-to-day public-lands management.

Obama rejected the coalition's proposal. His final version of the monument was roughly 500,000 acres smaller than the 1.9 million acres the tribes wanted. Although Beaudreau said tribal activists were disappointed, you'd never know it from their public statements.

Bears Ears is now commonly described as the first national monument ever created at the request of a coalition of Indigenous tribes. Contributions of the Public Lands Council have been recognized only as part of Bishop's grand plan.

Cooperative management arrangements with tribal governments are voluntary and common within the NPS with about 80 currently in place, according to Sams. Many tribes choose not to participate.

There are currently only four parks, monuments or preserves that have full-blown, fully legal co-management arrangements with tribes. They are Canyon de Chelly National Monument, located within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation in Arizona; Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Southeast Alaska; Grand Portage National Monument, within the boundaries of the Grand Portage Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota; and Big Cypress National Preserve in Florida.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument's unique enabling legislation preserves some land and mineral rights for the Navajo Nation. An Agreement for Cooperative Management of Canyon de Chelly was negotiated and signed by the Navajo Nation president, NPS park superintendent and Bureau of Indian Affairs regional area director (BIA is an agency within Interior).

The process involved extensive and on-going tribal consultation and community involvement, according to Sams. It's far from over.

__________

Toward true "co-management" in Montana

Part 4

Almost 1,000 miles to the north, the Blackfeet Nation and

its non-Native allies – Montana's Sen. Jon Tester, Glacier-Two Medicine Alliance

and National Parks Conservation Association – are not using the Antiquities Act

as a conservation tool. Instead, they're working to codify into law protections

and gain tribal rights to fully co-manage with federal land managers the Badger-Two

Medicine area adjacent to Glacier National Park.

The groups are pushing for a solution that would permanently protect the land from threats like oil and gas drilling and motorized and non-motorized vehicles, such as mountain bikes.

Badger-Two Medicine is the cultural backbone of the Blackfeet. It's considered sacred, the Blackfeet's source of knowledge and wisdom. It's where the tribe's origin stories were born and their ceremonies are held.

It's the last unmarred place the Blackfeet have to continue their way of life.

"We've never been given power to help co-manage our ancestral homelands," said Tarissa Spoonhunter, a Blackfeet assistant professor at Central Wyoming College. "We've been denied our rights to this land for so long, but we still have the relationship to it."

The bill introduced by Tester in 2020 to create a new designation for Badger-Two Medicine, a cultural heritage area, so far hasn't gained any traction.

Martin Nie, director of University of Montana's Bolle Center for People and Forests, is skeptical of the strategy. He said Congress would be unlikely to give tribes full control of public land, but having land management plans of BLM and Forest Service that require better consultation with tribes – even giving tribes the power to veto activities they oppose – could be a bridge to eventual co-management.

"The term 'co-management' can be controversial; it's in some dispute; it's very politicized," said Nie. "But what it does mean? It provides the tribe a more proactive and substantive, meaningful engagement in terms of how to manage public lands."

At a conference several years ago on the university's campus in Missoula, Nie gave examples in which different versions of co-management have been put in place. A prominent example is Washington tribes' active participation in the management of salmon runs in Pacific Northwest rivers. But that required a century-long struggle to work out the particulars that allowed the tribes to restore their traditions.

The National Bison Range north of Missoula on the Flathead Indian Reservation provides a different framework. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of the Department of Interior oversees the range but contracts with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes to carry out certain tasks. It's an uneasy situation, though, because the CSKT have expressed their desire to manage the range themselves.

"This is a weaker form of co-management. I don't even know if I want to call it that," Nei said. "(Possible CSKT management) has been terribly controversial, and one of the reasons is that (the range) never had a comprehensive conservation plan, no plan detailing how the Bison Range had to be administered. So there was some mistrust about how this place might be managed in the future."

The controversy involves several issues, including racial and cultural undercurrents, Nie said. Some people have even questioned whether transferring complete control of areas like the Bison Range or the Badger-Two Medicine to tribes would constitute a public land giveaway, and they worry it could open the door to those wanting to transfer federal lands to the states.

But if management plans spell out how agencies are expected to work with tribes, it could give tribes a better seat at the table, Nie said. And plans can dispel any racially motivated suspicions because everyone knows what to expect.

"(The details) can be negotiated," Nie said. "Critics of co-management might say 'I'm not going to give authority to the Blackfeet to co-manage anything unless I know how the place is going to be managed.' If you get a meaningful plan, then you have some insurance."

Blackfeet members in the audience said they don't support Nie's version of co-management because the federal government always has the final say. Just having a seat at the table doesn't go far enough.

"I don't see where (this kind of) co-management increases the tribal position. I think we need more experimentation with repatriation to enable and allow tribal management. If co-management could equate to that sort of scenario, we may have some sort of progress. Until then, it's just a gloss," said a Blackfeet woman.

__________

Tribal perspectives at the forefront

Part 5

Biden's proclamation in October resurrected and even expanded Obama's Bears Ears National Monument. A temporary management plan was put into place two months later. The interim plan guides policy decisions until a formal plan is adopted, probably two years out, according to BLM's timeline.

BLM and Forest Service staff in Utah said it mirrors Obama's in most ways and even Trump's to a certain extent – at least the parts that remained protected by monument status after he shrunk its footprint by roughly 85 percent.

And all three iterations of Bears Ears National Monument granted the five tribes a chance to offer policy guidance through creation of an entity called the Bears Ears Commission.

Biden, however, went a step further than his predecessors by granting tribes status a notch higher than myriad other stakeholders. It was demonstrated in an up-close-and-personal way at the formal ceremony in June, between high-level federal land managers and members of the tribal commission, to sign the cooperative management agreement.

Attending in the flesh were Tracy Stone-Manning, director of BLM, and Homer L. Wilkes, under-secretary of Natural Resources and Environment within the Agriculture Department (Forest Service).

"This is an important step as we move forward together to ensure that Tribal expertise and traditional perspectives remain at the forefront of our joint decision-making for the Bears Ears National Monument," said Stone-Manning at the ceremony held just outside the monument at the White Mesa, Utah, community of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe.

No other stakeholder group has been granted similar status, a politically charged acknowledgment rooted in the fact that the five tribes consider the area sacred. Artifacts of their ancient ancestors, tens of thousands, remain scattered across the landscape, some remarkably intact, mostly unprotected despite being located within monument boundaries.

The tribes' de facto claims of ownership stretch across "time immemorial," using Secretary Haaland's phrase.

It's been a long time coming.

Over the years, environmental groups, Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), the Wasatch Mountain Club, the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Defense Council and more than 200 other national and regional conservation organizations associated with the Utah Wilderness Coalition have tried to get their massive America's Red Rock Wilderness off the ground. Various iterations of it have been introduced into Congress every year since 1989. Although the efforts have cost tens of thousands of dollars, they have mostly only cemented the reputation of SUWA and the others as "defenders" who Protect Wild Utah.

In 2012, a 1.4 million-acre Greater Canyonlands National Monument was proposed. It would've encircled Canyonlands National Park. Same result. A bold idea couldn't overcome Republican opposition and, this time, the caution of Obama's Interior secretary, Ken Salazar, who expected consensus among ever-feuding factions before going forward.

In 2011, a coffee-table style book, Diné Bikéyah, outlined a tribal perspective on land use.

Native American spiritual and cultural sensibilities never figured prominently in any of those proposals. Then in 2010, a few Navajos rallied, notably brothers Kenneth and Mark Maryboy and Willie Grayeyes, after a call from former U.S. Sen. Bob Bennett (R-Utah) and launched their own initiative with financial and technical assistance from the nonprofit Round River Conservation Studies, based in Salt Lake City, as well as the David and Lucile Packard Foundation. Under Round River's direction, the group became Utah Diné Bikéyah and took an assertive, high-profile lead: Leonard Lee, vice chairman of the group, remarked, "We don't consider ourselves as stakeholders. … We're the landlord."

Many of the non-Native, big-time nonprofits behind America's Red Rock Wilderness and Greater Canyonlands National Monument stayed in the background this time around.

Preservation of American Indian culture along with its spiritual underpinnings proved to be a winner – at least until Democrat Hillary Clinton unexpectedly (to many of her supporters) lost her bid for president of the United States.

Nothing UDB did before about 2014 came close to what happened afterward, however inadvertently, to stress the fragile landscape of southeastern Utah, accelerate potential damage to sacred archaeological sites and boost tourism.

The Maryboys and Grayeyes, longtime activists and politicians, became celebrities of sorts in Indian County and founts of Indigenous Weltanschauung as their organization morphed into a powerful, extraordinarily gifted and ambitious multiracial team of young lawyers-to-be, graduate students, field organizers and passionate volunteers.

UDB was the Indigenous public face of a sophisticated multi-year, multimillion-dollar PR and political campaign that was national in scope. Kenneth Maryboy and Grayeyes are currently San Juan County commissioners who represent a strip of the county within the Navajo Nation and parts farther north.

The organization's ability to raise money has been remarkable. From 2014, when the Internal Revenue Service granted UDB tax-exempt status and its donor base grew exponentially, through 2020 (the most recent filings), the organization reported revenues totaling $6,381,985, according to Form 990s on file with the IRS.

In October 2015, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition and, in close association with UDB, submitted a monument proposal to Obama's Interior Department. Obama created the 1.3 million-acre Bears Ears National Monument just before he left office. President Trump shrunk it by 85 percent 11 months later. Then, keeping a campaign promise, Biden restored Obama's version in October 2021.

__________

Safeguarding objects and values, not access for recreation

Part 6

Deep within Biden's monument-founding documents lies verbiage that Gary Torres, former BLM Canyon Country District manager, in a briefing to members of the Monument Advisory Committee, MAC, referred to as "nuanced" changes in how Bears Ears would be managed.

The BLM and Forest Service will prioritize protection of "objects" within the monument and "values" associated with the monument, which could affect management of outdoor recreation , especially dispersed camping. According to comments of BLM staff and MAC members, vegetation and archaeological sites have been damaged.

Other activities have exacerbated the problem. Popular ATV and off-road driving and climbing, whose practitioners often attempt to park as close as possible to favorite routes regardless of possible damage to cultural sites, immediately come to mind. And the growing popularity of electricity-assisted mountain biking , particularly the fat-tired, high-torque variety, and gravel biking, currently legal on mostly forgotten mining roads, has opened up more remote parts of the backcountry. Many of those areas of archaeological significance yet to be professionally surveyed. Their damage would be permanent.

The agencies are in the process of identifying those "objects" requiring enhanced protection. Kamran Zafar, an attorney with the nonprofit Grand Canyon Trust , offered a comment in October 2020 to federal land managers that seemed to summarize Biden's current approach: "Cultural resources really need to be thought of, and any damaging activity should take a back seat.” His employer has contributed substantial financial and technical assistance to the creation of Bears Ears over the past few years.

Details:

- According to the Biden proclamation: "The State and Field Office staff will ensure that management of the monument conserves, protects, and restores the objects and values of historic and scientific interest …"

- It defines the entire Bears Ears landscape as an "object" deserving of monument protection: "… while the monument area is replete with diverse opportunities for recreation, … those activities are not themselves objects of historic and scientific interest designated for protection."

- BLM's standard "multiple use" obligations are scrapped, at least until a formal Bears Ears management plan is adopted: "Multiple uses are allowed only to the extent they are consistent with the protection of the objects and values within the monument."

- The kicker: "BLM-UT should consider taking appropriate action with regard to any such activities and uses that it has determined to be incompatible with the protection of objects and values for which the monument has been designated, …"

- And finally, there's this directive to the cash-strapped BLM: "The agency should also ensure that any activity or use that it approves includes adequate monitoring to ensure protection of monument objects and values."

Less significant perhaps, but nevertheless important as indicative of a new regulatory day dawning in Biden's Utah BLM and Forest Service, is that an employee of the Bears Ears Commission will work out of BLM's Monticello office, according to a BLM staffer. The embedded tribal representative would be in a position to communicate first-hand information on the inner workings of the bureaucracy.

No other interest group has been granted similar "fly-on-the-wall" status.

____________

Historical suspicions

Part 7

It's easy to cast a jaded eye toward this latest turn of events heralded nationally by high-level federal land managers, several of whom are Native American, as Biden's reset of the federal government's historically dismal record on relations with Indian Country.

"I wish I had a crystal ball to say it's going to work, and this is how it's going to be. This is brand-new, never been done before with tribes, specifically in southeastern Utah. So that's something we're just going to have to work with and see how it turns out," Mark Maryboy, one of the co-founders of Utah Diné Bikéyah, told High Country News.

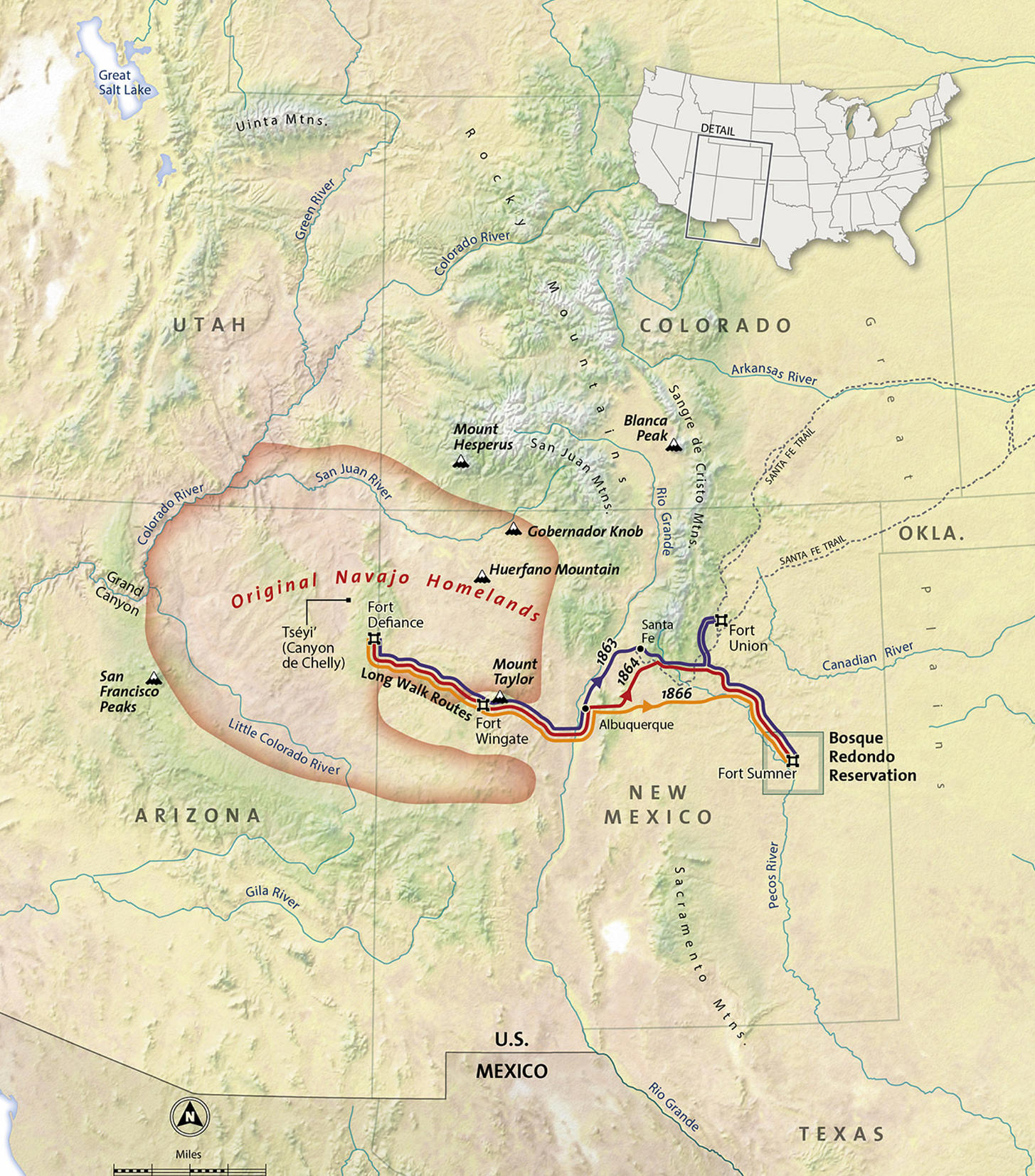

After all, the horror of "The Long Walk," a forced relocation of 250- to 450-miles during and just after the Civil War of more than 10,000 Diné (Navajo) to the desolate Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner, N.M., is still told and re-told to young and old on the Navajo Nation.

Several Navajo bands escaped the ethnic cleansing by taking refuge in the (still) virtually inaccessible canyons just north of the San Juan River, which has been identified by the Smithsonian Institution as part of the "Original Navajo Homelands" now commonly referred to as "Bears Ears."

Effective federal management to protect the region's artifacts, unique geological formations, plants and wildlife would have to overcome deeply ingrained suspicions – not only held by Navajos, but descendants of Mormon colonists who settled the area in 1880. They're among the most vocal (and politically powerful in Utah) critics of monument creation.

Yet it would be easy to persuade anyone who has made the random discovery of 1,000-year-old pottery in the cranny of a red-rock cliff, or trekked up the sandstone bluffs inside or adjacent to Canyonlands National Park at sunset, or spent a deathly silent, crystalline night staring at the canopy of creation to give it a try.

___________

Somewhat related:

Ping-pong protection: Is anything on the horizon that will truly safeguard Bears Ears?

Beyond the familiar apocalyptic boilerplate: About that drilling near Labyrinth Canyon

Designate it, publicize it and they will come … and destroy it: Of untouchable rhetoric and the fight against overcrowded tourism at home and abroad (Well, not so much at home)

The Grand Staircase Story: Morality of mining, no-compromise environmentalists, unreliable sources

Same as it ever was: Culture appropriation and displacement in the best of the West